By now, I think it should be obvious why I have prefaced this third post with the first. I have, throughout this mini-series, attempted to reconstruct the common understanding of the purpose and nature of the Torah. If you haven’t already read the first post, I strongly recommend that you do. Ultimately, I intend to make clear that the Torah is not a comprehensive legal collection that provides ways to actualize the full intrinsic good of God’s eternal law (which is what some anti-Christians may be prone to think). Or, in simpler terms, the Torah alone does not describe God’s ideal, and does not tell you how to create it.

A Short Preface

A brilliant Old Testament scholar, John Walton, Professor Emeritus at Wheaton College makes a point on page 96 of his book – The Lost World of the Israelite Conquest:

“…The Bible as Scripture – that is, as the divinely inspired authoritative word of God – does not provide us with moral knowledge because God’s purpose in providing it for us does not include teaching us how to be moral.”

I agree with John Walton that this ultimate good will never be actualised on this fallen Earth, but I have some contentions with the idea that the Old Testament cannot at all teach us how to be moral. I would not argue that the Israelites did this, but if you use the New Testament – this, and Christ, highlight the spirit of the Law as the true guiding principle – I would say that the New Testament reveals the purpose of the Old. The Torah (remember, this is only the first five books – the Pentateuch) is intended to maintain order in the ANE society and to ‘introduce’ Yahweh to the nations, with Israel as his vassal and Him as their Suzerain.

A fair question may arise from critics – what is this ‘ultimate good’? The intrinsic moral good that humans ought to be looking for, and I think makes the most sense of the Biblical data, I would argue, is God’s ultimate will, or more formally:

The Good:

- is what is representative of the ultimate order of God’s kingdom. It is manifested through his necessarily active will (not commands) and can be characterised as the true actualisation of a subject’s potential – how well a subject reflects its ordained purpose.

- It is therefore compatible with the privation theory of evil, where evil, a lack of true order, is disorder.

*This definition is not exhaustive, and there are a couple of extra things I would ordinarily add, but I don’t want to draw us too far away from the main point of this post.

Anyone who is more fluent in metaethics will see that I am quite sympathetic to the theory of natural law, and as per this view, God regulating or permitting slavery is not an admission that he believes slavery to be a ‘good’ thing (by my definition above), nor do I need to contend that it is. The descriptive nature of most laws outside of the 10 commandments effectively means that we can confidently say that these laws do not represent God’s ideal – a society containing slavery is not his ideal, and it is him regulating the existence of the ANE model with the idea of gradual progress in mind, not immediate reform.

Further, amid caste systems and undeveloped agriculture, industry, housing, trade and debt, birth control, and differing practices of neighbouring cultures. Israel was presented with situations that pretty much necessitated labourers. The aims of civilization in such a time of everything being so undeveloped times cannot be dismissed. Progressing toward civilization demands a system of meeting the labour required for development.

Due to this, slavery would form a mode of employment security, as working for yourself would likely have been an untenable position for most due to the scarcity of opportunity. Any economist reading this would be familiar with the drawbacks of specialisation. A division of labour would be much more profitable.

I would argue that what we see in the Torah is a complex interplay between Divine action and Human freedom, God having to compromise due to the nature of man, and man necessarily realising the majesty of God. One such example of compromise (along with that given in Numbers 27 in previous posts in this series) is Israel receiving a king in Saul, when they were not supposed to (1 Samuel 8:6-9).

Although there are ‘regulations’ against beating and abusing slaves, I do question the plausibility of the claim that “masters constantly abused slaves” except for reasons of pure wickedness. Given that slaves brought financial prosperity to their owners, the quality of work they would do would be dependent on the money invested into them (eating, housing etc.). With the wisdom from Exodus and Leviticus being upheld, I do wonder if it is reasonable to suggest that people were willing to seriously damage these people that they had invested such money into (thereby reducing their economic output).

So, to reiterate, my point of this post is not to prove that Biblical slavery was ‘good’, or objectively ‘ideal’, because (1) I don’t think it was and (2) it didn’t need to be. Similarly to my previous post, I simply accept it as ‘necessary’ (which can have a ‘neutral’ or ‘negative’ “moral value”). As such, trying to show whether Biblical slavery was good or not is completely missing the point of the Torah. However, I intend to provide a more ‘humane’ way of reading the popular passages in Exodus, Leviticus, and Deuteronomy that are popular in anti-Christian rhetoric, and how you can understand these passages better considering Israelite and ANE culture, but firstly…

Slave or Servant?

The first question to ask is which is more probable – ‘slave’, or ‘servant’.

One source reckons that:

“Based on statistics, the distinction between ‘servant’ and ‘slave’ can be determined by conducting an extensive lexical search on how the verbal cognate Avadעבד is expressed throughout the scriptures. Out of 291 occurrences, only 20 instances unambiguously refer to subjugation, making it a 6.87% probability. On the other hand, eved עבד is contextually linked to being a chattel slave in various verses (e.g., Gen 15:13, Gen 15:14, Jer 25:11, Jer 25:14, Exod 1:13, Exod 1:14, Exod 6:5, 2 Kgs 25:24, Jer 27:11, Jer 40:9, Deut 28:48, Isa 14:13, Jer 17:4, Jer 27:6, Jer 27:11, Jer 28:14, Jer 30:8, Jer 40:9, Ezek 29:18). Hence, ‘servant’ is the default term because 93% of the time the root of eved עבד is in reference to voluntary labor.”

Section B. Slave or Servant – Biblical Slavery Exhaustively Debunked – Tom Hohlweg

Naturally, such a claim seems to be subjective, and the above source does not list the 271 other occurrences where the verbal cognate ‘Avadעבד’ is used, however, if such claim is true, it will help us to greatly reduce our biases regarding the nature of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible), and it would give us a strong prior probability that the verses which will soon be in question are not referring to negatively-connotated slaves, but rather servants – for figures such as Jesus (Isa 53), Moses (Num 12:7), and David (Psalm 78:70-2) were referred to as ‘eved’’s.

Therefore, the statement that “Hebrew has no vocabulary of slavery, only servanthood” (Alex Motyer, the Message of Exodus p.239), would seem very plausible, with Raymond Westbrook, who holds a doctorate of Assyriology concurring, saying that “the meaning servant seems more appropriate, or perhaps the designation semi-free. It comprises every person who is subject to orders or dependent on another but nonetheless has a certain independence within his own sphere of active” (A History of Ancient Near Eastern Law, 2003, volume 1, p.632).

Laura Culbertson (a doctoral scholar of Near Eastern Studies) tells us that servants “could act to preserve or transform their quality of life… Slavery was thus not a unilaterally downward social sentence, with many slaves rising along with their owners”. She also tells us that “household affiliation itself could be equivalent to protection and secure legal status…rather than a social death”, and therefore household affiliation was neither dishonourable nor subject to exploitation. It therefore seems the most plausible, by the admission of the Oriental Institute Seminar, that Ancient Near Eastern ‘slavery’ can much more be summarized as ‘service’. “Thus on result of the oriental Institute Seminar is a consensus that scholars should dispense with the slave-free dichotomy”.

Culberson. L. (2011). Slaves and Households in the Near East.

Some people may take contention with the idea of being ‘owned’, but putting Christian theology of sin aside, God refers to his people as slaves/servants (Leviticus 25:55). “Adonai” – means Lord, master, and owner. To the Jews, this was not only respectable but desirable – it meant that you had the privilege of being rescued from Egypt and belonging to Adonai – this concept is shown at the end of Romans 6:17-18. Paul in Romans 1:1 refers to himself as a ‘slave’ (gk. doulos) to Christ. I think the mutual ownership of and belonging between husband and wife is something beautiful, so in my opinion, the “ownership” of another being is not something intrinsically evil. Whether it is disordered or not is contingent upon what said ownership entails.

Ultimately, whether you wish to use the word ‘slave’ or ‘servant’ from here on out is up to you, my point is more fundamental – that it is unreasonable to approach these texts with the modern negative connotations that come with the word ‘slave’ (i.e., zero rights, zero freedom etc.) inspired by transatlantic antebellum chattel slavery.

The following will be exhaustive, but I think it’s necessary since this is a pressing topic.

Exodus 21

This chapter deals with regulations for Hebrew debt slaves, along with general slave regulations. As an aside, I have seen some critics claim that Exodus 21 refers to debt slaves only, since it talks about them going free. It is true that the laws in Exodus 21:2-6 specifically address Hebrew debt servants, outlining a six-year service period after which they are to be freed without payment. It also discusses the conditions under which they might remain with their master if they so choose. Verses 7-11 deal with female servants and their rights and protections, but the rest of the chapter goes on to describe various laws regarding personal injury and property rights, which pertain to broader social and civil matters beyond servitude. Exodus 21 includes instructions on debt servitude, but it is not limited to that; it covers a broader range of servitude and legal issues. Considering that this chapter comes right after the prescriptive, universal 10 commandments, I would argue that the principles about how to deal with slave death (from v.12 onwards) also apply to how to deal with the deaths of all types of servants. Therefore, the claim of the critic is not an accurate representation of the text.

Verse 4-6 (the ‘given wife’ and the ear piercing):

This seems quite unfair, but some helpful points can be made as to how marriages functioned in the ANE.

In the Hebrew Bible, masters were more like investors rather than traditional slave masters, as seen in Genesis 17:23,27. The logic is well explained in “Genesis To Deuteronomy Vol 1 ((Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary)”:

- “When a free man gave a wife to another man who owed him something, certain conditions applied to that marriage. The man in the inferior position was often a pledge (one who worked as a servant, not a slave, and whose services functioned as security or collateral for a debt that was owed) or a debt-slave, as here in Exodus. Typically, the pledge or debt-slave could take his wife – and any children she had borne him – only by satisfying particular requirements.”

With the existence of ‘bride prices’ (a sum of money or quantity of goods given to a bride’s family by that of the groom in some tribal societies), the servant had to compensate the master. Someone “sold” the bride to the groom for a bride price and no dowry (the opposite direction of payment) system existed – this was a very business-oriented ordeal. Thus, a better rendition of these rules, from Douglas Stewart’s “Exodus: An Exegetical and Theological Exposition of Holy Scripture” is as follows:

- If the man and woman were already married when they came into the contract, the servant would have had built into the contract some provisions for keeping the spouse, i.e., the boss (master) needs to take account of housing, feeding and clothing the spouse too.

- If the boss gave a wife (which would most likely be a woman already serving him) to the servant, there had to be a compensation for the costs for that woman servant while already serving him. Her potential to provide children was also an asset, considered part of her worth. Therefore, as a protection for the boss’ investment in his female worker. A male worker could not simply “walk away with” his bride and children upon his own release from a service after six years.

A potential problem seems to pop up almost immediately – “Doesn’t this give the male worker no options with his master and family?” No, Dr Stuart addresses this possibility:

- He could wait for his wife and children to finish their service.

- My comment: The text does not say that the children and wife were necessarily the master’s in perpetuity and also does not state that they belonged to the master in more than a legal sense, as such, I question the plausibility of claims of the form ‘a man could be used to breed slaves’. This claim does not seem to be supported by the wider body of the text for two reasons:

- Familial Considerations: The provision regarding the wife is likely intended to ensure the well-being and stability of the servant’s household during the period of servitude (initially 6 years). Providing a wife could contribute to the servant’s integration into the community and provide companionship and support. Also, if the child were to be ‘forced into labour’, rather than only be legally attached to his father’s master, then the man and woman could simply abstain from having sex until the man’s release, in which he could purchase his wife’s release and then have children.

- Inheritance and Lineage: Any children born to the servant and his wife during the period of servitude may have been considered part of the master’s household, but this does not necessarily imply exploitation or forced labor. Instead, it reflects the complexities of inheritance and lineage within ancient Israelite society.

- My comment: The text does not say that the children and wife were necessarily the master’s in perpetuity and also does not state that they belonged to the master in more than a legal sense, as such, I question the plausibility of claims of the form ‘a man could be used to breed slaves’. This claim does not seem to be supported by the wider body of the text for two reasons:

- He could find a good job elsewhere and earn enough to buy their freedom.

- He could, if he so desired, agree to work permanently for his boss (as v.6 states).

Some people also may have contention with the “pierc[ing] his ear with an awl”, but Dr Raymond Westbrook, in his book “Law from the Tigris to the Tiber: The Writings of Raymond Westbrook – Volume 1” that “ear-piercing is not especially painful, nor was it regarded in the ancient Near East as disfiguring or degrading; it was common for free men and women to wear earrings in pierced ears”.

Verse 7 (‘if a man sells his daughter as a female servant’):

Scholar W.H.Thompson, in his book on “Pauline Slave Welfare…” informs us that this female servant, an ‘amah’, is unlikely to already be married and that she is more probably being sold into a house that she will be married into (i.e., she will marry the son of the Master of this new house).

Bringing J.E Smith’s work in “The Ten Commandments Reconsidered” on pages 98-99 and G.D. Miller’s “Marriage in the Book of Tobit”, we see that this type of practice was common enough in the Ancient Near East to have its own name – a ‘möhar’. A möhar intended to secure the daughter’s welfare and provide economic relief for the family (given that some fathers sold their daughters because of an inability to provide for them) – and therefore, this verse can be seen as a ‘forward payment’ of this woman’s bride price, as the möhar was also compensation granted for the family for the loss of the girl as an economic asset (everyone had to work those days, situations were dire – Gen 24:11-6, Gen 29:6, 1 Samuel 9:11, Ruth 2:2).

It is also true that this was not the only way to acquire a wife, given Jacob’s committing to serve Laban for 14 years in Genesis 29:15. Though Jacob’s case was an exception, not the norm.

Another attribute of a möhar was that it promoted the stability of marriage and strengthened the links between families being married. Some critics may contend that the woman was reduced to the status of a slave, however, the following verses rebut this very criticism, as they guard her rights and protect her from sexual exploitation. For actual evidence of this sort of arrangement, I encourage you to check the Nuzi tablets.

Verses 8-11 (‘if she does not please her master…’):

This verse and the following ones provide strong support for the previous points made. It only makes sense to have ‘dealt deceitfully’ if the woman was intended to be married into the house. J.E. Smith tells us that the better rendering of this verse is “if she displeases her master so that he does not betrothe her to himself, he shall allow her to be redeemed” – though this is very close to the translation given in the NET translation. This tells us that if the marriage didn’t happen as expected, the möhar was returned to the master and the daughter was returned to the family she came from. To round up, verse 9 clarifies that this woman, when within the house of her master, was granted ‘daughter’ status, again dispelling modern connotations of servanthood in the Israelite ANE.

Verse 16 (prohibition against slave trafficking):

Some critics pick at this verse to make the point that this prohibition was only relevant to the Israelites and not foreigners. However, the Hebrew root ‘gnb’ of “steal” is derived from the 8th Commandment, making this prohibition a universal (prescriptive) code, not local (descriptive), as we have already argued.

Verses 20-7 (slave abuse and murder):

Generally speaking, the critic’s argument is as follows:

“Beating and surviving means nothing, you can beat a slave within an inch of their life if you don’t remove an ‘eye’ or a ‘tooth’. The master isn’t even killed for murder. Also, look at the end of verse 21! “He is his money”! How much clearer can pure ownership be!”

- Imaginary critic (I’m just trying to steelman their position)

Let’s go through the passage in question slowly. We will address each claim in this quote but not in order, as certain parts need to be gotten to before others.

20-21:

a. “The master isn’t even killed for murder.”

The first point to make is that it is far more plausible that masters received the death penalty for murdering their servants:

- The Womens Evangelical Commentary enlightens us as to what the Hebrew “naqomnaqam” may mean. P.168 reads: “The owner who caused a slave’s death must be punished (Hb. Naqomnaqam, “avenged”, used only here in Exodus; the infinitive absolute form gives the ruling extra force, as if to say “without appeal”; cp 2 Kings 9:7), his life was forfeited”.

- Numbers 35:18 tells us that anyone who commits homicide with a weapon of wood receives the death penalty. Although this specific verse is not in Exodus, the point in the verse is stressed that “the murderer must be put to death”. With this verse also being in the Torah, it does count towards being pro-death penalty for murder in this context.

- Konrad Schmid in the research publication “Money as God?” tells us on page 272 that: “it is also possible to interpret the regulations in Exodus 21:20 as a specification of the overall rule in Exodus 21:12: “Whoever strikes a person mortally, shall be put to death.” Already the Samaritan Pentateuch reads “shall be put to death” instead of “shall be punished[[or avenged]]” and thus clarified the meaning. Understood in this way, the intentions of Exodus 21:20 seem to be the following: the death penalty applies even to cases where the victim is a slave… Leviticus 26:25 interprets nqm with the expression “to bring the sword upon you,” i.e., killing.”.

Konrad Schmid continues:

“Furthermore, the specification “the slave is the owner’s [money]” again suggests that the interpretation of Exodus 21:20 as a monetary payment is hardly possible. Compensatory payments are only provided in the CC [Covenant Code] for cases involving injuries, but not intention (yrybn “quarrel”) or homicide”

As a matter of fact, the principle that a master receiving consequences for harming their own slave is actually only found here in Exodus when compared with contemporary Ancient Near Eastern texts. Arguably, relatively speaking, this a monumentous progression, considering it seems to prohibit (or have as its premise the prohibition of) a ‘pure ownership’ mindset that may have been pervading through ANE cultures concerning the relation between masters and their own slaves.

b. “Beating and surviving means nothing, you can beat a slave within an inch of their life…”

The classic knee-jerk reaction from Biblical sceptics (e.g., Mr “I’m not convinced” Matt Dillahunty) is that Exodus 21:21 implies that if their servant survived two or three days after a beating, the master wouldn’t be punished, but scholarship dismisses the abject ad-hoc reasoning. The phrase “two or three days” is a mere formality, serving as a rhetorical device to summon as many witnesses as possible for a fair deliberation of justice, as Jonathan Burnside and others make clear in the book “God, Justice and Society – Aspects of Law and Legality in the Bible (p.118)”:

“Fourth, biblical justice was supposed to operate against a background of regard for due process. Ensuring that sentences were of sound moral character was one aspect of this (noted above); rules of evidence were another. According to Numbers 35:30, a single witness was inadequate. Deuteronomy 17:6 (= Deuteronomy 19:15) states that someone should only be put to death on the testimony of two or more [literally, ‘three’] witnesses” (JPS). The formula is an intensifying rhetorical device that emphasizes the need for as many witnesses as possible. The greater the number, the safer the conviction (cf. the similar formula of “a day or two” of Exodus 21:21, which could mean two days, a week, or several years). The requirement to “inquire diligently” and ensure that “the thing [is] certain” (Deuteronomy 17:4) means that the “two or three witnesses” formula could never be reduced to a numbers game especially if the witnesses themselves were of doubtful character. We should not, therefore, regard 1 Kings 21:1-15 (the Naboth incident) as demonstrating the weakness of biblical rules of evidence. Accepting the testimony of “two scoundrels” (verses 10-13; JPS) was itself an outrage and at odds with the purpose of Deuteronomy 19:15.”

c. ““He is his money”! How much clearer can pure ownership be!”

The next line of attack comes with the accusation that ‘keseph’ in verse 21 means chattel (pure and total ownership), but W.H. Thompson corrects this mistaken standpoint, saying that “The word…”silver”… in the explanatory clause of 21:21 does not necessitate chattel status; it is simply the ancient unit of exchange”. This tells us that just because the master owned the slave’s services, it does not therefore necessitate that the master owned the slave as a possession outright.

d. “as long as you don’t remove an ‘eye’ or a ‘tooth’”

23-27 (only a tooth or an eye?):

NET reading:

“’ “If a man strikes the eye of his male servant or his female servant so that he destroys it, he will let the servant go free as compensation for the eye. If he knocks out the tooth of his male servant or his female servant, he will let the servant go free as compensation for the tooth.‘”

It may seem clear that this verse is extremely specific and ad-hoc, which may seem confusing. I say to you, that that interpretation should leave you confused.

Notice the quote below by ANE scholar Christopher Wright: He points out that damaging a tooth and an eye is emblematic of any unwarranted assault. Then, he makes the distinction between the humanity of the slave and the financial value of the servant (we must define terms better because, as we have previously shown, ‘property’ can be misleading):

“The inclusion of the ‘tooth’ indicates that the law does not intend only grievous bodily harm, but any unwarranted assault. The basic humanity of the slave is given precedence over his property status”

Christopher J. H. Wright, God’s People in God’s Land: Family, Land, and Property in the Old Testament, 243.

Christopher makes another important characterization regarding the legal status of slaves. They, too, like anyone else, had legal rights, which included the right to take their master to court if they were wronged (including abuse):

“To allow, if we were to have any meaningful legal (as distinct from merely charitable) force, must presuppose that there were some circumstances in which a slave could appeal to judicial authority against his own master, that in some situations a slave could have definite legal status as a person, notwithstanding his normal status as purchased property.”

Christopher J. H. Wright, God’s People in God’s Land: Family, Land, and Property in the Old Testament, 244.

Verses 28-32 (the compensation goes to the master??):

The final line of attack fires here, with the accusation that because the master is compensated for the death of the slave, instead of the slave’s family, the slave was considered chattel. However, Hittitologist Harry Hofner and scholar Richard Averbeck bust that misconception. I will summarize points from these two sources:

- The Old Testament Law for the Life of the Church – Richard Averbeck. (p.204)

- Israel: Ancient Kingdom or Late Invention? – Daniel L. Block (p.152-153)

Servants were seen as part of the master’s household and participated in religious duties; hence they were more than mere property. They were “perceived as slaves belonging to the households of their masters, and thus entitled to participate in all their religious rites along with the master’s family.” The payment for a servant’s death was not an appraisal of the human value (imago-dei) but rather an “appraisal of their economic value.” So, concerning Exodus 21:32, Richard Averbeck and Harry Hoffner suggest that the law differentiated between negligent homicide and manslaughter and that compensation was an economic matter. They state that “the owner and master are two different subjects,” highlighting that the payment was to the master and not for the loss of human life per se. The thirty shekels of silver is a “specific amount of the compensatory payment that the traditional price of a slave (30 shekels of silver).” These scholars discuss the principle of “graduated payment according to the ‘value of the victim,’” which is tied to the concept of restitution and is common in the ancient Near East, not just in biblical law. Thus, these texts highlight that “this principle of graduated payment according to the ‘value of the victim’… is indeed the principle that governs remedies for wrongful death in almost every jurisdiction today.” Noting verse 30, we see that generally “if the victim’s family would accept monetary compensation”, the slave’s life could be redeemed by paying whatever they demanded, and the ox’s owner was able to raise.

Leviticus 25:44-6:

Leviticus 25:35-46 provides a detailed set of guidelines concerning the treatment of the poor and the practice of servitude among the Israelites, expanding upon and modifying the principles outlined in Exodus 21:2-6. This passage is part of the broader legislative framework that includes the Year of Jubilee, which is intended to prevent the long-term impoverishment and servitude of Israelites within their community. It also distinguishes between indentured servants and slaves purchased from other nations.

One thing that may seem confusing might be the lengthening of the possible maximum length of servitude here (from 6 to 50 years). The lengthening of the period of servitude in Leviticus, by tying it to the Jubilee cycle rather than a fixed six-year term as in Exodus, can be understood in the context of the social and economic, objectives of the Jubilee system:

- The Jubilee system allowed for a comprehensive economic reset every 50 years, which included the release of servants and the return of property to original family owners. By extending the period of servitude to potentially longer than six years, it provided a structured time frame in which an individual could work off their debts or regain economic stability without the pressure of an imminent release that might leave them without means.

- A longer period before the Jubilee could better facilitate the integration of servants into the households they served, providing them with sustained support and stability in times of economic hardship. This longer integration could be particularly beneficial in agricultural societies where cycles of planting and harvesting required stable, long-term planning and labour.

Secondly, it should also be noticed that the language in Leviticus markedly changes from that used in Exodus. The indentured Israelite is to be treated as a ‘hired worker’ rather than an ‘eved’ that we constantly saw in Exodus 21. This could mean one of two things:

- This level of treatment can be read ‘back’ into Exodus, suggesting that the ‘eved’ of Exodus 21, although treated better than those in Leviticus 25:44-6, is also seen by its writers as a ‘hired worker’. I think this is reasonable, but I don’t think this clearly grasps the text.

- There is a three-tiered hierarchy of service. We have at the top, those of Leviticus 25:35-44, who are ‘hired workers’ and ‘hired workers’ alone. Secondly, we have those of Exodus 21, who although are not reduced to mere ‘objects’ during their term, are below their master’s on the social hierarchy. Third, we have those of Leviticus 25:44-6, who are servants/slaves that can permanently belong to households but ought not be treated as the Israelites were in Egypt. I think this better understands the text.

Lastly, it should also be noted that this situation was not necessarily a guarantee – Leviticus 25:47+ tells us that this indentured servant could be redeemed by his brethren before the Jubilee. As such, I think such a (possibly long) time of servitude was meant as an incentive to get people to manage their money well, since bailing somebody out likely would have been expensive.

Let me first paste it in my favourite translation of the verses we care about, and then I will try to write the common anti-Christian argument, similarly to how I did in the previous section:

‘ “‘As for your male and female slaves who may belong to you – you may buy male and female slaves from the nations all around you. Also you may buy slaves from the children of the foreigners who reside with you, and from their families that are with you, whom they have fathered in your land, they may become your property. You may give them as inheritance to your children after you to possess as property. You may enslave them perpetually. However, as for your brothers the Israelites, no man may rule over his brother harshly. ‘

“It’s crappy to live in a system where you own other people. Where you remove somebody else’s agency entirely. Isn’t this also utterly racist? Where is the progression? How can you have PERPETUAL ownership, that’s so evil.”

- “It’s crappy to live in a system where you own other people. Where you remove somebody else’s agency entirely. Isn’t this also utterly racist?”

We have already made the case in “Slave or Servant” that it is not entirely accurate to impress our modern connotations of ownership upon slavery in the ANE. Leviticus 25 presents the option of Israelites acquiring and keeping foreign slaves permanently, but it is presented as an opportunity, not a command. It is correct that the verses in question use the phrase “you may give them as inheritance to your children after you to possess as property”, but I will propose a more nuanced view of what this verse entails. Again, I am not saying that this is God’s ideal – I just intend to explain the ANE logic in question here, considering that this specific practice was quite common in ancient Mesapotamia.

Part 1a – The Distinction – God’s view:

I will briefly use a parallel argument to elucidate how God sees the intrinsic value of these people. In Isaiah 56:6-7, we see God making special promises regarding foreigners – promising to bring them to his Holy Mountain, Zion, where the Messiah will take residence for all of eternity (Psalm 2:6). The NET uses the word ‘foreigners’ but it’s not clear to me why this wouldn’t include servants also. Dalit Rom-Shiloni, on page 124 of “Exclusive Inclusivity: Identity Conflicts between the Exiles and the People who Remained” confirms that these people are not Israelites, saying:

“Although in relation to the Levites, this terminology suggests their cultic function, Isa 56:1-8 uses this terminology to suggest the incorporation of these foreigners into the religious lay community) נִלְוִים, נִלְוֵי אֱלִילִים (v. 6a). The loyalty requirements in vv. 6b-7 do not imply any cultic, “Levitical” function for those foreigners (in contrast to Isa. 66:21). These verses simply welcome foreigners into the general pious community of Yahwist worshipers, the community of Israel (v.8).”

The word used for foreigner in verse 6 is “nekar” coming from the Hebrew word “nakar”. This means that “nekar” and “nokri”, which are analogous and also derived from “nakar”, have the same etymological root. With “nokri” being a synonym for “goi”:

“Goyim, a Hebrew word used in the Jewish Scripture to refer to non-Jewish pagan groups. Colloquially, all non-Jewish nations came to be called goyim. According to the Jewish Encyclopedia, the word “Gentile” corresponds to the late Hebrew goi, a synonym for nokri, signifying “stranger” “non-Jew”” –Honaïda Ghanim: The Oxford Handbook of the Sociology of the Middle East (P.118)

…we can say that the foreigner in Leviticus 25:44 is analogous to a “nekar” or “nokri”, which are the same people that God promised to bring to his Holy Mountain, so we have established that God shows them no partiality.

A critic may argue that I am reading ‘Isaiah’’s understanding of this law “back” into the contemporary understanding (given that Isaiah could have, and this is debated, been written up to 600 years later) and therefore not understanding how the contemporary Israelites understood this verse, but this critic may be misunderstanding my point for now. In this mini section:

- So far, I am only trying to show God’s view of these ‘aliens’, not the Israelites’.

- Secondly, this critic would likely be making my point about moral progress for me. If Isaiah (along with God) saw this law as such, then the idea of moral progress seems to be shown with the distinction between contemporary (1300BC) Israelite views and views around the time of Isaiah (8th century B.C).

- This might also show that the truth of Galatians 3:28 might have had an underdeveloped, but existent form in the Old Covenant.

Part 1b – The Distinction – Israel’s view:

Verses such as Exodus 23:12, Leviticus 19:10, Deuteronomy 14:21, 29 and 24:14 tell us that the Israelites were exhorted to go out of their way to protect the immigrants’ interests, and we also note that Leviticus 25:47 tells us that ‘aliens’ could obtain property, grow in wealth, and take native-born Israelites as indentured servants. This seems to show a consistent ideology. But regardless of this, there is an obvious distinction between the possible ‘contracts’ for the Israelites and the foreigner. I think the reasons for this could be as follows:

- Social cohesion: By prohibiting ‘harsh’ treatment of fellow Israelites and limiting permanent servitude to non-Israelites, the laws could foster a stronger sense of community and solidarity among Israelites. This internal cohesion was crucial for the survival and identity of the nation, especially considering the external pressures from surrounding peoples and empires.

- Theological reflection of the covenant: Israel’s laws were believed to be given by God and reflected the covenantal relationship between God and Israel. Israelites were seen as God’s chosen people, set apart for a special relationship with Him. This special status could have been reflected in the way they were required to treat one another. As foreign as this sounds to us, cultural identity was a BIG thing in the ancient world.

- Remembrance of past servitude: Israelites were commanded to remember their own experience of slavery in Egypt and were frequently reminded not to oppress the stranger because they had been strangers in a foreign land (as in Leviticus 19:34). Someone might contend that these two verses are not talking about the same people, but I think this would entail a contradiction, which is something that would have been obvious to the scribes that wrote the law. The ‘aliens’ in Leviticus 25 were still foreigners so would still fall under this law.

As such I think it is more plausible that the ‘harshness’ is seen more as perpetual (1) ‘unpreferable’ and/or (2) ‘strenuous’ labour work from which the Israelites are exempt. Foreigners who’s service is acquired through slavery are to be shown love but can be subject to (remember, this is not a command, but an opportunity) this unpleasant perpetual labour situation (which the Israelites would find ‘harsh’ as noted by the verse). The fact that the Israelites are exempt from this type of perpetual contract does not diminish the humanity of the other aliens in their situation as Leviticus 19:33-4 (and, Exodus 22:21) seems to corroborate, and we have already argued above with relation to Isaiah.

- Control of foreign influence: By differentiating between Israelites and non-Israelites in matters of servitude, there might have been an attempt to control the cultural and religious influences that could come from within the household. This was part of a broader concern in ancient Israelite society to maintain religious purity and prevent the adoption of foreign gods and practices.

Part 2: A return to ‘ownership’:

Let us now tackle the latter parts of this verse. Peter H. W. Lau expounds on the word ‘buy’ in most English translations. This word ‘qanah’ (‘qnh’) in Hebrew denotes redemptive language – not slave trading language. Presumably, the Israelites were redeeming the foreigners out of slavery, rather than institutionalizing it.

“The unique circumstances in the Ruth narrative also explain the only use of the verb qnh, “acquire,” in the context of marriage. It is used regarding both the field and Ruth (w.4, 5, 8, 9, 10). The word has a wide range of meanings, and in commercial contexts, it refers to the purchase of objects, such as a field or threshing floor (Gen 33:19; Sam 24:21), or people (e.g., Gen 39:1; Neh 5:8), especially relevant to the case at hand is the use of qnh in texts related to redemption: the redemption of land and the purchase of slaves (Lev 25) and Jeremiah’s redemption of family land (Jer 32:1-15). Ruth refers to herself as “your handmaid” (‘amateka; 3:9), and although Boaz is not “buying” her in the same way as described in Lev 25:44 (also āmā), perhaps the use of qnh in the Ruth narrative was influenced by Lev 25:44.0* Rabbinic texts will use qnh in association with marriage (including levirate), especially in contexts where there are other transactions in which qnh is used for a “purchase”.”

Lau, P. H. (2023). The Book of Ruth.

One may contend that women were seen as ‘property’ in the Israelite world, using a verse such as Exodus 20:17 (where women seemed to be ‘lumped in’ with belongings), but this, as have many criticisms, seems to be very unnuanced, and as such, quite inaccurate. Women in ancient Israelite society had a complex status that was marked by legal dependency and social roles largely defined by a patriarchal structure. While they were often under the authority of their male relatives and, as we have seen, marriage involved a form of contract, it would be an oversimplification to describe women solely as property. Instead, they held important familial and societal roles and were afforded certain protections under the law, reflecting a multifaceted view of womanhood within their cultural and historical context.

- “Where is the progression? How can you have PERPETUAL ownership, that’s so evil.”

We have already discriminated between pure, outright ownership and servanthood, but it seems clear that this problem has come up again. We see that, per my ‘three tiered’ definition of Israelite Servitude I gave before, that Israel has progressed with regard to treatment of their own people. I’ll outsource the rest of the effort to Jay Skylar – Professor of Old Testament and VP of Academics at Covenant Theological Seminary:

“Because these servants were permanent, the text draws a parallel between them and the Israelites’ land holdings (which were also permanent). They are therefore described in a similar way (as a “holding”) and could be passed on to children (as an “inheritance”): “You may have them as a holding, and you may pass them as an inheritance to your children after you to have as a perpetual holding: you may make them serve as permanent servants” (25:45b-46b). Again, the language strikes us as offensive, since it makes these servants sound a little more than property. But we actually use the same type of language today in business contexts.

“Trading” sports players (as we might speak of trading stocks), transferring employees (as we might speak of transferring money), or describing them as “assets” (as we might describe holdings). Such language is not intended to diminish a person’s humanity; it is simply a convention used in the context of business transactions. In this case, the servant’s permanent servitude to the household has been purchased, and that does not end simply because the head of the household dies (just as a debt owed to a bank does not end when the bank president dies). To use a different language, the person’s servitude is like a lifelong mortgage owed to the family, and as such, it may be “transferred” (“inherited”) when they take over the household. Even here, however, it must be remembered that the servant is a נְחָלָה, a word often used to describe land over which the Israelites have certain rights but do not fully own (see further comments at 25:10). The same is true of permanent servants from the nations. The Israelites have certain rights (the servant’s service) but do not own them as “property” to use in any way they see fit, just as the land ultimately belonged to the Lord, so do these servants, who bear his image and must be treated with due respect”

The parallel is not perfect. Sports persons are paid much more these days than servants are paid in their contemporary society, but the legal action of trading and passing on someone’s services is similar.

It should also be noted that the LORD calls Himself the property ‘Achuzzah’ and the inheritance ‘Nachalah’ of Israel in Ezekiel 44:28. If the Lord refers to Himself as property and inheritance, there was no nefarious intention in using these words:

‘ “‘This will be their inheritance: I am their inheritance, and you must give them no property in Israel; I am their property. ‘

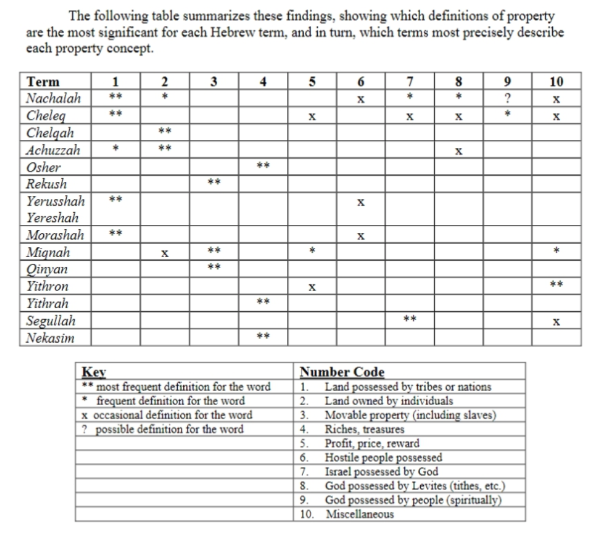

We are nearing the end of this section, so let us view how property language was used in the Bible. The following is a diagram put forth by John A. Battle as part of his specialized research on property language in the Hebrew Bible – notice how ‘achuzzah’ (property, v.45) does not qualify for movable property (pure slaves) or hostile people possessed:

A point can also be made about ‘adoption and manumission’:

Ancient Near East literature contains a wealth of rich source material regarding the legal process known as ‘adoption and manumission.’ One of the most explicit examples can be found in the story of Abraham’s foreign servant, ‘Eliezer,’ illustrating how an outsider of Israel could be adopted and become an integral part of a household for the master’s lifetime or until the jubilee lands. Notably, upon the master’s death, the adoptee would inherit the master’s house and possessions. William Dumbrell’s research outlines Eliezer’s adoption and birth into Abraham’s house, shedding light on this process. ANE scholarship provides context to the nature of slaves, revealing them as individuals bonded by debt (not necessarily financial) rather than mere chattel, often being born into the household. These slaves voluntarily chose to be adopted by a master through a legal process. It is evident that within their historical context, these practices were not inherently malevolent. It is true that “manumission” means ‘to release’ but remember that the verse doesn’t command the perpetual binding – it only presents it as an opportunity. Therefore, I don’t see a good reason why a similar practice could not in any sense be attributed to Leviticus 25:44-6.

Lastly, using dictionary.com, ‘Chattel Slavery’ is defined as:

- the enslaving and owning of human beings and their offspring as property, able to be bought, sold, and forced to work without wages, as distinguished from other systems of forced, unpaid, or low-wage labour also considered to be slavery.

The fact that this verse only permits the Israelites’ bequeathing to ‘sons’ tells us that these slaves belonged to the household of their masters, and as such, had a household affiliation – which would rule out the possibility of ‘trading’ these slaves in a chattel manner between households, provinces, states or more – and ‘selling’ is a crucial criteria for labelling this as chattel slavery (as the main point of chattel practice is to gain profit). I have alsoalready made the point that ruthless rule with starvation is irrational, so it’s not very clear how well ‘force’ can be applied in forcing these slaves to work. Again, in my section ‘Slave or Servant’ Laura Culbertson tells us that slaves in an Ancient Near Eastern society “could act to preserve or transform their quality of life… Slavery was thus not a unilaterally downward social sentence, with many slaves rising along with their owners”. For this reason, I think that, using modern definitions, this is race-based perpetual servanthood, rather than race-based chattel slavery (in which you would be able to not only do anything you want to these slaves, along with selling them to whatever households, states, and provinces you want to).

Deuteronomy 20-21:

The following section will deal with female war captives. Many misconceptions arise regarding Israel’s war practices and, right off the bat, we’re going to dismiss the first.

Misconception: “Israel practised sexual slavery!”

Response: No, they didn’t. Sexual slavery was not permitted during war for Israelites, because, similarly to how many Ancient Wars were fought (as Sumerian texts tell us), Israelite soldiers were consecrated before they fought. We see in Exodus 19:14-15 that when approaching Yahweh at Mount Sinai – the people are instructed to wash their clothes and abstain from all sexual intercourse. With God being present with the Israelites (with the Ark of the Covenant) during the war (Numbers 10:35-6, Joshua 6:7-13. 1 Samuel 4:3-11, 11:11), in a legislative sense, Israelite soldiers were not permitted to perform sexual acts during the war. Explicit evidence is seen for this in 1 Samuel 21:4, where the priest says to David “I don’t have any ordinary bread at my disposal. Only holy bread is available, and then only if your soldiers have abstained from sexual relations with women.”.

Israelites were certainly not allowed to perform any sexual acts within the temple as part of the worship of Yahweh (Lev 21:7, 9; Num 15:39; 25:1-4; Deut 23:17-18; 1 Kings 14:24; 15:12; 22:46; Hos 4:4; 2 Maccabees 6:4; see also Rev 2:14, 20).

Now for the actual ‘slavery’. Deuteronomy 20:10-11 reads:

“’ When you approach a city to wage war against it, offer it terms of peace. If it accepts your terms and submits to you, all the people found in it will become your slaves.’”

The rendering here isn’t very accurate, but the NET comments tell us that the verse in Hebrew was translated as “become as a vassal and will serve you”. If you have read the first post in this series, you would be familiar with the Suzerain-Vassal dynamic, and vassals were not slaves as defined in modern times but rather were obliged to pay royal taxes and perform public works.

John Currid, Chancellor’s Professor of Old Testament at Reformed Theological Seminary, tells us in his 2006 Study Commentary on Deuteronomy, that Deuteronomy 21:12-14 is the apodosis to the protasis of Deuteronomy 20:10-11 (i.e., it is the “then you can do this” following the prior “if this happens”):

“First, the woman is to be taken into the man’s house, and there she is to be treated kindly and with dignity. After she is taken into the home, she is to shave her head, pare her nails and remove her captive garb. These acts are to symbolize that she no longer has the status of captive slave. The Septuagint and the Dead Sea Scrolls (11QT6:3.12-13) both depict the Israelite man as performing these acts upon the woman as a declaration of her new status. Deut 21:14. ‘And it shall be that if you do not take pleasure in her, then you shall send her out according to her wishes. But you shall certainly not sell her for money. You shall not oppress her because you have humbled her.’ The protasis of this law begins with the word ‘if’ and it indicates that not all marriages with captive women will work out. Husbands may terminate such marriages if they so desire. This is a formal divorce proceeding, and the verb ‘send… out’ is often used of divorce (see 22:19,29). The apodosis, beginning with the word ‘then’, spells out the manner in which the woman is to be treated. First, when she is divorced she will remain a free woman, and she cannot be reduced to slavery. A rejected wife, foreign or not, cannot become a slave. The husband cannot make money out of her by selling her into slavery. She is free. The husband is not to ‘oppress’ her. The exact meaning of this verb is uncertain; it appears only here and in Deuteronomy 24:7 in the entire Bible. It has been translated in various ways: ‘deal tyrannically’, ‘enslave’ (Philo), ‘set aside’ or ‘disregard’ (Septuagint), and ‘trade’ (Targums).”

Criticism: A critic may contend that “the phrase used for “you have had your way with her” is used elsewhere in the Bible twelve times, and sometimes it DOES mean rape, and therefore that Deuteronomy is effectively legislating rape! GAME OVER!” This person would likely be referring to 2 Sam 13:12, 14, 22; Lam 5:11; Judg 19:24; 20:5. Twice does it refer to violating an unbetrothed girl (Gen 34:2; Deut 22:29), but it also refers to adulterous sex with a consenting woman (Deut 22:24); once to sexual intercourse with a woman on her menstrual period (Ez 22:10), and once to incest (Ez 22:11).

The issue with this interpretation is the fact that all of these cases refer to cases of sexual immorality – i.e., they are, in some way illicit and are seen as debasing the woman. We have already seen that Deuteronomy 22:22+ legislates against rape in the previous post, and since this is a legal scenario, it follows that this act of taking a woman to be your wife, waiting the mourning period and then being permitted to sleep with her and casting her out (effectively reducing her to an object) is deemed as sexual immorality, instead of the misconception that rape is being legislated. We also note that Exodus 21:16-17 legislates against kidnapping an individual, telling us that the man was not allowed to “steal” this woman against her will for his desires, and further, the man being forced to wait a month, having seen the woman without her hair and beauty ornaments tell us that this law was intended to help ensure that her captor wanted to marry her for love rather than lust. Isaiah 3:18-24 attests to a high valuation of beauty ornaments.

Some more reasons why this is not referring to rape are as follows:

- The Hebrew word ‘anah’ (humbled/humiliated) is multifaceted. The Targum Jonathan (an Aramaic translation of the prophets) employs the word “intercourse” suggesting that my theory about the contemporary understanding of the sexual relation between the man and the woman is true.

- If the female captive was violated (and therefore ‘damaged goods’ as the ANE society would have seen it), the texts likely would have used “taw-may” as used in Genesis 34:27 (concerning Dinah being raped by Shechem).

- Deuteronomy 8:2, 3 and 16 employ the verb ‘anah’ in the PIEL verbal stem (the most flexible stem formation in Biblical Hebrew), which clearly refers to God humiliating Israel and therefore humbling them, but we know that he didn’t impose Himself or rape Israel.

Rebuttal: “Then what is the shame? What does it mean to ‘humble’ her?”

Since divorce was considered rejection, the wife subjected to it would “lose face” in addition to the already humiliating event of having become a wife through conquest.

An extra line of defence of the fact that the woman’s consent was necessary to becoming an Israelite wife can also be seen in Numbers 30:9. This section talks about vows. We know that this woman would be both a widow and without a father (per the conquest), and as such, her vows would stand without the presence of a ‘head’ (father or husband). As such, the woman could not be forced into marriage if she didn’t want to be married.

Another line of progression?

It can be argued that what we see in Deuteronomy 23:15-16 is another line of ‘monumentous’ progression (similarly to what I stated for Exodus 21:20-21). Again, nowhere in other ANE legal collections do we see this principle of ‘not returning a runaway slave’. This would provide another line of evidence for the idea of moral progression.

One could argue that this sort of stipulation only holds for slaves who run away from specific regions, and is therefore effectively a command not to hold extradition treaties with other nations – which is a position which Dr Joshua Bowen, an Assyriologist holds. I am happy to grant that this is a possibility, but it still seems to me that the underlying principle of ‘not returning a foreigner’ (in a ‘hard’ society with a scarcity of resources) still provides a ‘sanctuary’ for runaway slaves – which was the opinion of Harry Hofner:

“Deuteronomy 23:15-16 concerns slaves in neighboring countries (e.g., Tyre, Sidon, Aram, Ammon, Moab, Edom, Philistia, Egypt) who escaped and entered Israel seeking sanctuary. These instructions prohibited Israelites from extraditing them to their foreign masters. Ancient Near Eastern treaty documents that included clauses requiring the return of fugitives serve as the background to Deut 23:15-16. Escaped slaves and political rebels represented two different classes of fugitives. However, it seems that the purpose of this law was not only to discourage such treaties (undoubtedly any such treaty in the era of Moses would have included such a stipulation), but also to protect slaves who fled to God’s people for protection from oppressive treatment by brutal masters. Israel was to be a place where oppressed people from other lands could find refuge, just as God freed them from enslavement in Egypt.“

Israel: Ancient Kingdom or Late Invention? – Daniel L. Block (p.154)

Corvée Labour:

Despite all that has been said, you’d be unsurprised to hear that ‘online atheists’’ issues don’t stop here. Forced/conscripted labour is described in 1 Kings 7:1-12 for the new palace Solomon builds. Remember, we aren’t talking about the moral legitimacy of Solomon building the palace or slavery, we are just trying to understand, contextually, the nature of these agreements. We have already talked about the Suzerain treaty between Israel and God, but Israel also formed such treaties with other nations. The labour operated on a national level rather than a personal one, and these labour agreements were pre-arranged agreements between vassals and suzerains. It should also be noted that God punished Israel for breaching their treaty in 2 Samuel 21:1 and the King of Israel was required to compensate the Gibeonites for their loss (2 Samuel 21:2-9) – entailing a higher level of obligation on the Suzerain than the vassal.

“The distinctive emphasis of the treaty was on the superior party, the suzerain. In this arrangement the suzerain agrees to make certain provisions for the vassal. He agrees to defend the vassal in the case of attack, along with permitting the existence of the vassal nation. In addition, the suzerain has the right to take tribute from the vassal at any time. The vassal, for his part, agrees to a position of servanthood but not slavery. Vassals honor the suzerain with tribute and material goods“

Longman, T. I. (2013). The Baker Illustrated Bible Dictionary. Baker Publishing Group

“FYI: God does not allow the Israelites to empire build. People they come against typically attack, and/or raid Israel first. The “forced labor” is typically a lord/vassal treaty, which exists between countries and not slavery on a personal level.”

A New Believer’s Bible Commentary: Genesis-Deuteronomy. Barret, J (2013) (p.199)

A Miscellaneous Text – 2 Kings 4:1

Nothing needs to be said in an attempt to vindicate this scenario. The labour of people and households could be used as collateral to guard against debt as is seen in this verse. I’ll let the scholars handle this one, I’m getting tired.

“We already saw in Chapter 3 that in the cuneiform tradition debt-slaves were not to be regarded as the property of their creditors, since the creditor has only purchased the service capacity for work (Arbeitskraft) of the debt-slaves (This view is also advocated by Riesener, Der Stamm TIP, pp. 1, 130; cf. also Rashi, ad. Loc.).”

Chirichigno, G. C. (1993). Debt slavery in Israel and the Ancient Near East (p. 179). Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

“Households in Israel were entitled to land grants. Although households held title to the land in perpetuity, it was often lost to creditors. Monarchs taxed households into crippling debt. Rich households made loans to poor households to pay their taxes, but secured these loans by taking their land and the labor of their members as collateral. When households defaulted, creditors foreclosed on the land and sold its men, women, and children as slaves (2 Kgs 4:1). Legally, creditors were not buying land or selling slaves, just holding the land as collateral and collecting the wages of its household to repay the debt (Lev 25:35-46; 2 Kgs 4:1; Neh 5:1-5).”

Strauss, M. L. (2011). How to Read the Bible in Changing Times: Understanding and Applying God’s Word Today (p. 121). Baker Publishing Group.

New Testament

1 Peter 2:18, Ephesians 6:5-9, Titus 2:9 and Colossians 3:22:

You would think that the New Testament, arguably the moral guideline for western society today would be so clearly against slavery during the Roman rule of Judea, but according to our anti-Christian friends, Christians can’t even catch a break here! The first thing to point out is that the predominant viewpoint among New Testament commentators is that these texts aren’t referring to Jewish slavery, but rather Roman slavery.

“The view that these concisely formulated teachings have adapted a tradition whose real background can be assigned to a Greco-Roman environment has found almost unanimous acceptance among New Testament specialists. “

Stuckenbruck, L. T (2013). Religions and Trade Religious Formation, Transformation and Cross-Cultural Exchange Between East and West (p.357)

The second point to be made is that Peter and Paul are being tactical and prudent. With slavery being the bedrock of the Roman economy, if early Christians had immediately clearly opposed it, they would have been spawn-killed. There was already hatred between the Jews and the Romans, and we already know that Nero had no issue blaming Christians for the Great Fire of Rome, you can only imagine the diabolical things that would have happened if Christians immediately went for the foundation of the military superpower ruling over them.

“The idea of slavery as the foundation of the Roman economy needs to be stressed, and this foundation may well lie at the heart of early Christian exhortation to remain submissive to masters. If it is true that slavery was the central labor force of the Roman economy, it follows that if Christians became known for opposing the institution, the Roman authorities would immediately, and perhaps even irreparably, damage the movement. Put differently, it was important to the survival of Christianity for its slaves to be good slaves. Since this was the case, one motive for Peter’s exhortation would have been the desire to survive as a movement. Peter’s exhortation to live under the order as slaves emerges, then, from this economic context. Herein finds them that they are to do this “with all respect,” or “with deepest respect.” He insists that they are to show the same “deep respect” even to “those who are harsh.” Peter wants the Christian slave community to manifest a kind of behavior that transcends the norm of society and demonstrates its supernatural origins. In so doing, the economy will not be threatened, and the Christians will be seen favorably.”

Guthrie, G.H,. Nystrom, D.P, McKnight, S,.Burge., M.,Keener – NIVAC Bundle 8: General Epistles, Revelation

Luke 12:47-8 (???):

Yes. Some people stoop this low, but likely due to a lack of understanding.

“Slave managers and even cases of slaves owning slaves are known from the Roman period. In most of the parables of Jesus that involves slaves, a slave who fails in his task is demoted, exiled, beaten, or executed (Matt 18:23-35; 21:33-41; 25:14-30). Luke 12:47-48 displays a standard that any Roman master would have been familiar with: “The servant who knows the master’s will and does not get ready or does not do what the master wants will be beaten with many blows. But the one who does not know and does things deserving punishment will be beaten with few blows.” Slaves who were successful gained more responsibility rather than manumission (Matt 25:14-30). Jesus did not endorse slavery with these stories, but used their familiar context to teach about the kingdom of God”

Yamauchi, E. M., & Wilson, M. R. (2017). Dictionary of Daily Life in Biblical & Post-biblical Antiquity (p. 1519). Hendrickson Publishers.

Now for the counter-case. Judeo-Christian values are what effectively led to the abolition of slavery (per modern connotations), but how did the New Testament ethic accomplish this?

Romans 16:7-9:

‘Andronicus’, ‘Amplias’ and ‘Urbanos’ were common slave names – and are the names of common workers with Paul. Considering Paul was Jewish, it follows that there was very reasonably no Jewish Christian slavery.

Galatians 3:28:

Slaves are, by definition, seen as inferior. However, Paul makes it abundantly clear that there is no inferiority/superiority in Christ. As the Christian message spreads – such an idea will render the slave/master hierarchy obsolete, as we have seen.

1 Corinthians 7:23:

The usage of the word ‘become’ here is significant. It implies consent and entails a previous ‘free’ status. Paul is, quite literally, telling the Corinthians to not become slaves.

Quite a strong case can be made using this verse, actually.

The verse says ‘do not become slaves of humans’. Furthermore, verse 21 does implore slaves, if they can do so wisely, to seek their freedom. Luke 17:1-4 is a direct condemnation of the one who causes another to sin and 1 Corinthians 8:13, a chapter later, is an echoing that Paul held that same sentiment as Luke. If ‘becoming a slave’ is contravening Paul’s command, how much worse is it for those who force others into slavery? Further, if all are equal under Christ (Galatians 3:28), and even enemies are to be loved (Matthew 5:43-44) all are made in God’s image, then it seems very difficult for Christians to justify any sort of forceful enslavement that would have persisted in first-century Judea.

My point here is not that the verse, alone, removed from context, stands a categorical declaration against slavery (i.e., “revolt against your masters and sow turmoil – immediately destroy the institution”, as Peter and Paul are quite adamant against that, for the survival of Christianity), but when read in the context of Christian principles, which can not be removed from it if you want to make a substantive point about the Christian Bible, Paul is instituting commands that thoroughly destabilise justification for any organic form of Christian slavery – i.e., it effectively becomes a direct command against taking and becoming slaves.

Colossians 4:1:

Paul exhorts Hellenized Jewish-Christian masters to be just and fair – for those who want to quote Colossians 3:22, please quote this also.

Rolling all the evidence together, we see that people are told not to become slaves, that they all hold equivalent value in Christ, that masters should treat their slaves fairly, and that Paul works at the same hierarchical level with people who can be reasonably concluded to be slaves. It’s therefore not surprising that these ideologies dissolved the Greco-Roman model of slavery.

So, does the Bible promote Slavery? No, that would be misreading its intention.

The Old Testament regulates/permits the Ancient Near Eastern practice of servanthood and redemption of those who have sold themselves into slavery while trying neither to immediately abolish it nor evaluate its moral status. Following the New Testament, Christianity led to the abolishment of slavery – which is the opinion of multiple historians, such as Tom Holland and Robert Fogel.

For those who wonder why Christianity didn’t immediately put an end to slavery, such would have been deeply implausible considering the Greco-Roman environment it was operating in. Christianity acted like a ‘depth-charge’. As such, it took a while for its truth to penetrate through to the bottom of society. I do have a few contentions with John Walton’s framework for moral epistemology, but I think he does a good job with the analogy of God ‘baking a cake’ – illustrating the concept of necessity, and that it should not always be equated with something intrinsically good:

“Although we should understand God’s actions as purposeful (that is, working toward a goal), we should not imagine that God furthers that goal by producing progress. We should not imagine that God is constantly shaping humanity to ever-higher levels of goodness or morality that will eventually achieve the ideal. Neither should we imagine that we represent the society that has actually achieved the ideal. An alternative model to understanding a process toward achieving a goal is what we could call procedure, as opposed to progress. In a procedural model, every iteration serves a different purpose toward a common goal, which could not be achieved without the completion of every step. The metaphor for a procedural model is the process of baking a cake. There is a final, ideal cake at the end, and some of the steps will more closely resemble it in terms of their attributes than others, but the various stages in the recipe are evaluated not on the basis of how closely they resemble the ideal, final cake but of how necessary they are to produce the final product.”

The Lost World of the Israelite Conquest (p.24) – John Walton

Although John distinguishes between ‘progress’ and ‘procedure’ – I would say that these two models are not mutually exclusive – given that ‘procedure’ naturally ‘progresses’ toward something.

I hope you found this helpful. If you have any questions/points/objections, feel free to leave them down below and I’ll try to get to them!

Thanks for reading,

P.S: This is an excellent dialogue that, if you made it this far, you’d likely be interested in seeing. It covers both perspectives of this topic.

Rookie